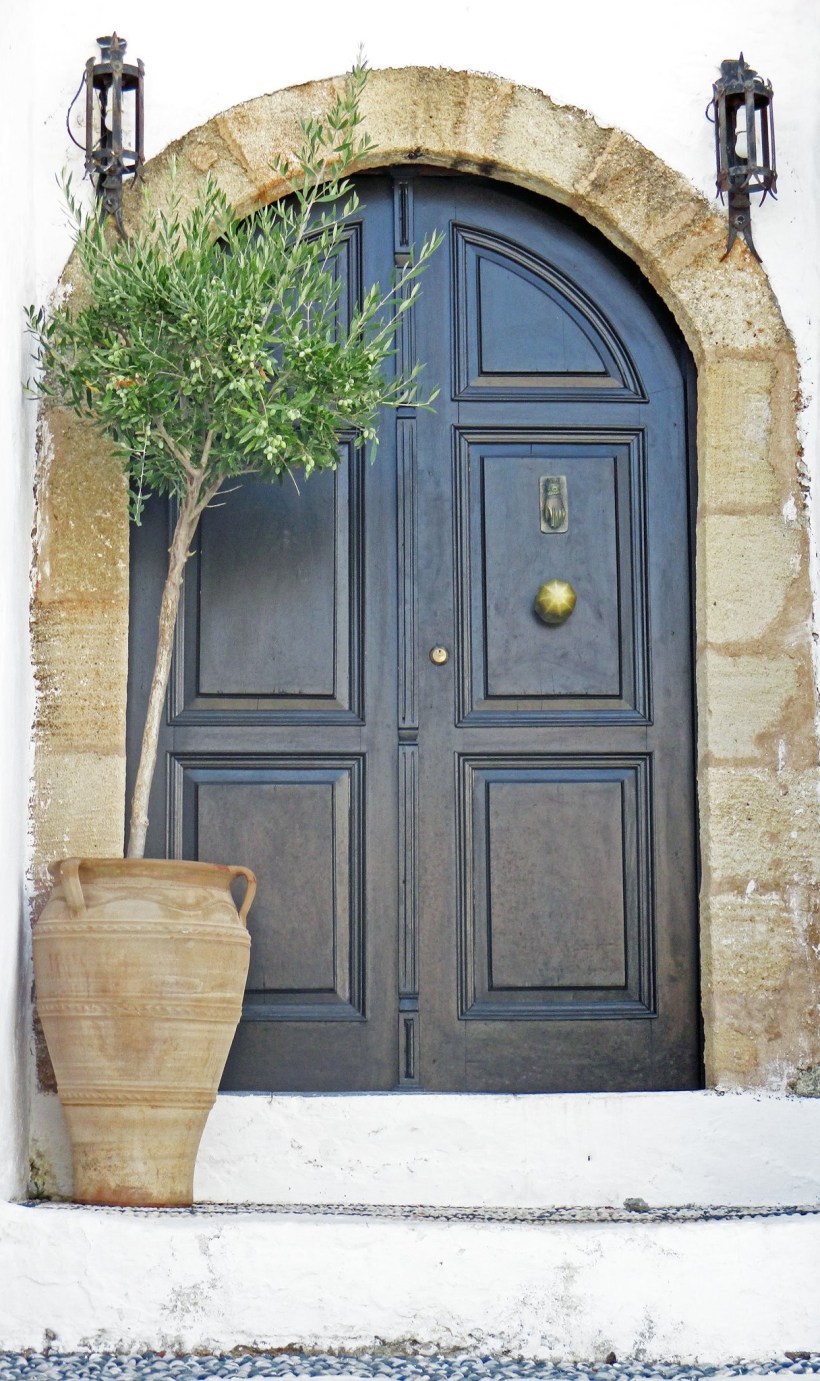

Surrrounding the family run Metohi Vai Taverna are herb gardens buzzing with bees and giving off the aroma of the indigenous plants growing there. In any nook on the paved terrace are pithoi planted with colourful, fragrant blooms. These complement the brightly coloured water jugs and flowers that adorn the tables. Interesting works of art, lovingly nurtured from driftwood smoothed by the sea and washed up on the local beaches, sit on tables, and bits of traditional ironware adorn niches in the old stone walls.

Rushwork umbrellas provide welcome shade from the burning sun. Despite the heat it is difficult to resist the delicacies on offer. I order far too much. A horta omelette and salad is followed by pork shanks marinaded and roasted in red wine vinegar, lemon juice, garlic and oregano, served with traditionally roasted potatoes in lemon juice. For the connosieur a full red would have been the order of the day but the heat and generous portions lead us to an ice-cold light, fruity house white so sharp it could cut glass.